How feedback changes everything.

"Details emerge more clearly as the fractal curve is re-drawn." - Ian Malcolm

In my previous article, I discussed one of the major aspects of systems - “process”. We looked at how processes are composed and that they are essentially deterministic. (i.e. given the same set of inputs, you get the same set of outputs.) This is all well and good in the world of theory, but as anyone who’s ever tried to build a piece of IKEA furniture has found… Processes often should work…but sometimes just… well… they just don’t. Theory always works in theory, but doesn’t always work in practice.

Well you’ll be thrilled to know that systems theory has a reason as to why this is the case - and this is where things start to get interesting.

At the core of any dynamic system (and therefore at the core of pretty much everything in the real world) is the concept of “feedback”.

Our health, wealth and happiness, the natural world, our economic and social systems are all both a product of and maintained by feedback loops. From the waves in the ocean to the way memes spread through digital networks. Feedback. Underlies. It. All.

Understanding feedback loops is vital as this gives us insight in to the hidden forces that really make systems “tick”.

Like many words in English - the term “feedback” has multiple meanings. As a result many people use the word feedback to describe a process, for example, there are all sorts of processes from annual pay reviews to marketing surveys that involve “gathering feedback“. This usually means “gathering inputs to a process” and as we discussed in the previous post - these processes have a start, inputs, decisions, steps and outputs.

Gather some feedback.

Assess the feedback.

Respond to the feedback.

This input in these cases might be better termed “information”, “perspectives”, “views” or “opinions” (as “feedback” has a more specific meaning in relation to systems which we’ll get to shortly). Here, given the same input “information“, and the same assessment steps executed consistently, the output response will be the same. Stable and deterministic. After all, who wants an unstable pay review process or an unpredictable marketing campaign?

Processes - by their nature - tend to take the happy well-trodden path. Existing in their abstract introspective world, they don’t need to worry that your alarm didn’t go off, that you set the oven at the wrong temperature or the fact the car wash down the road is out-of-order.

The point of a processes - to some degree - is that they are an abstraction and so don’t have to represent the nuances of reality to be useful. If it doesn’t work? Simply follow the process again and it’ll work next time.

Many business practices, academic theories and knowledge frameworks we use to reason about the world are process-oriented, and so don’t explicitly account for repetition or how that repetition may affect future execution of that process.

However, this is where reality tends to through a spanner in the works, because in practice, processes don’t operate in isolation. They all receive their input from somewhere and that somewhere is the “environment” in which they operate. They also generate output, and that output goes somewhere. That “somewhere” is - yep you guessed it - the environment again.

This continual interaction between a process and the environment that it works within creates a “feedback loop” in which a process causes changes to it’s environment and next time around, the process then takes those changes in again as input resulting in a loop.

These feedback loops are both:-

the natural product of continually repeated processes and also;

the source of stability or instability with a system.

To understand that second point we need to know that these loops come in two forms:- “Positive” and “Negative” feedback loops.

So, as I always like to end on a positive, let’s look at the negative form first.

Negative Feedback

A very simple example of this is a thermostat regulating the temperature of our room.

We can see here where process sits (in the orange box) within a feedback loop. So the thermostat - the process part of the feedback loop - is essentially…

Read the current temperature. (“input”)

If the current temperature is less than a target (which could either be an input or fixed at a comfortable temperature - e.g. 19°C) then…

turn the heater on to warm the room up… otherwise turn it off to let it cool down. (“output”)

But this process doesn’t repeat in isolation. It’s own output affects the environment in which it operates (i.e. the temperature of the room) which in turn affects it’s input temperature reading.

This repetitive cycle of “observe” and “take action” is the “loop” we’re talking about and you can see that process is only one of the interlinked parts in this wider dynamic system.

There a few extra bits of jargon here. Alongside “Process“ and “Environment“ which we’re already familiar with:-

“Effectors” essentially have an effect on the environment. In this case the heater, by being switched on, has an effect on the room by heating it up and;

“Sensors” take in information (in this case the temperature) from the environment.

Where all those component parts are working well together, this feedback “loop” has a stabilising effect on the rooms temperature, ultimately balancing at it’s target temperature. Nice and comfy!

This is an example of what’s called a “negative” feedback loop. These are sometimes referred to as “balancing” or “goal-seeking” loops which work to stabilise a system by counteracting (or negating) any deviations. Negative feedback is crucial for maintaining balance and preventing systems from spiralling out of control.

Other examples are blood sugar regulation, predator vs. prey population control in ecosystems, cruise control in cars and even social conformity.

Positive Feedback

The other type of feedback loop we regularly come across is a “positive” (or “exploding”) feedback loop.

Herd behaviour, flash floods, and mobs of Black Friday bargain hunters can all be explained through the lens of positive feedback loops and they can often take us by surprise.

Unlike negative feedback loops - these loops amplify change, leading to exponential growth or decline.

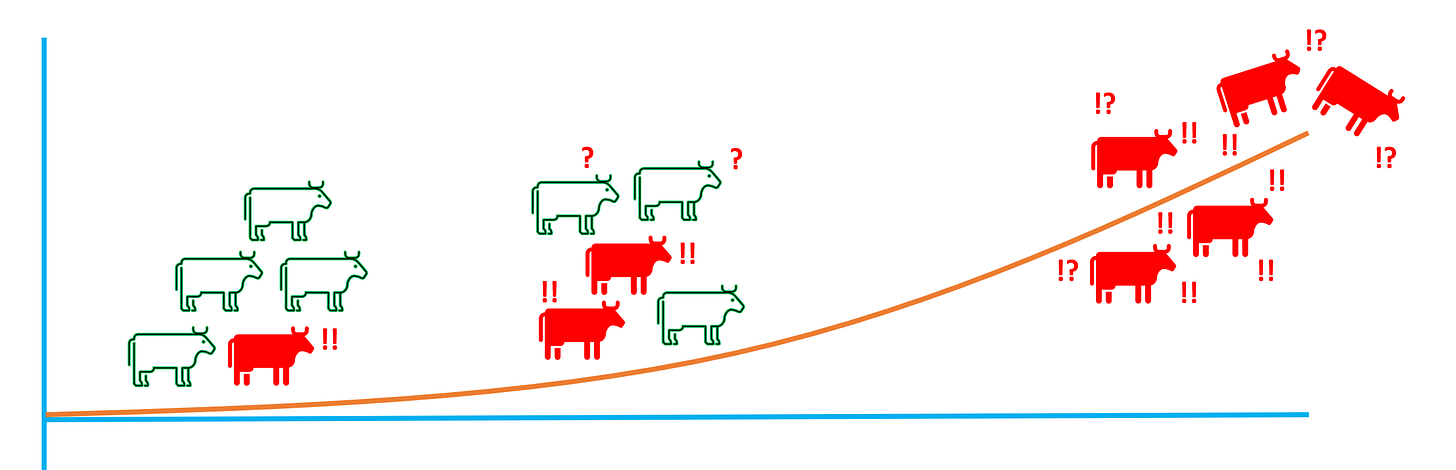

Thinking of how stampedes develop. You start with a nice calm heard of cows happily grazing in a sunny field…

An individual cow perceives a level of danger in the environment either:-

first hand - perhaps being startled by a butterfly or…

second hand - being startled by seeing other cows running around in panic without having to see what startled them in the first place.

Now depending upon whether they as an individual are startled by these observations, they then begin to run around in panic too.

This results in more cows in the herd running around - raising the overall level of danger in the heard ultimately resulting in absolute pandemonium and cows running around everywhere.

Here, instead of that causal loop having a negative, regulatory or balancing effect, it has an explosive effect. This continuous amplification cycle reinforces the herd panic response.

Positive feedback can also cause exponential collapse. For example, if a key species in an ecosystem dies out. If bees were to die out for example, we would lose all the plants that bees usually pollinate. All those animals that eat those plants would also struggle to find food. They in turn would reduce in number and eventually affect almost all living creatures.

So, Negative feedback results in regulation and positive feedback results in exponential change.

The types of simple example I’ve given often lead people to believe that:-

“Negative feedback” = “Regulation” results in “Stability” and that;

“Positive feedback” = “Exponential growth” results in “Instability”

However, whilst the former is true, the latter is not. Both types of feedback ultimately drive for stability, however the path to reach that stability is different.

Where negative feedback operates by carefully balancing environmental factors, positive feedback operates by shifting the environment out of it’s existing state to a new normal.

Sometimes, this new state is unsustainable due to other constraints (such as system capacity) which can cause a sudden failure of that new state. i.e. There are only so many cows to run around and they’ll eventually get tired.

But, for example, the network effect of technology adoption is also the result of a positive feedback loop - where the more people that use a technology, the more likely it is that others around them might use it too, pretty quickly, the "environment” has found a new base state and it’s very difficult to dislodge this widely adopted technology. We’ll cover this specific in more detail and talk about how you can use this to create momentum, in a future post.

So to sum up, feedback loops are a reality of dealing with changing environments but are often overlooked, with a focus placed more narrowly on the “process” part of the loop. This is easier to reason about in isolation (and designed processes are also perceived as much more within our control vs. the wider environment). Nonetheless, by understanding feedback loops beyond just the process component, we can explain why some processes lead to balance, control and stability and others end in noise and disarray.

You may have noticed that the two types of feedback I’ve described so far are still deterministic. (i.e. in the graphs above, you can see the wavy line of negative feedback and the curved line of the positive.)

However, the real world doesn’t always work in such a predictable way. And this is the topic of my next post and how an accidental discovery in the early 1960s led to an entirely new field of scientific study which has profound implications for how we think about systems and how we design and manage them.

I’m looking forward to seeing you there!

Thanks very much for reading and if you’d like to know when I next post, I’d really appreciate it if you subscribe using the button below.

Footnote: What does all this have to do with value creation? Well, we’ll get to that, but in the meantime - for all you folk at the intersection of financial AND systems thinkers - here’s something very abstract to ponder on. The 3 statement financial model (i.e. Income, Balance Sheet & Cashflow Statement) could be seen as a (very) complex specialisation of the 3-body problem. Sit back, relax and watch as everything you were taught back in business school descends in to chaos.